Collapse at Lake Chad: How Climate Stress Transforms Resources Into Flashpoints

Some geopolitical analysts call water “the oil of the twenty-first century,” with all the strategic and economic significance that this comparison connotes. The decline in rainfall levels, driven by climate change, reduces food production and intensifies competition over dwindling water supplies, exacerbating social, economic, and political tensions. Water scarcity fuels conflicts over control and access, leading to violence or deliberate resource manipulation. In the Sahel, climate change is a conflict amplifier. Current local, state, and international responses to these climate-related tensions are insufficient; water security should be integrated into broader frameworks and an international standard for transboundary water governance should be pursued.

Case Study: The Sahel

Water scarcity in the Sahel, a transitional region separating the Sahara Desert and the savannas of Sub-Saharan Africa, represents an existential crisis in an area historically plagued by weak governance and economic struggles. Today, over 20 million people in the Sahel engage in nomadic and pastoralist lifestyles, and have been for millennia. Through seasonal migration across national borders with their cattle—which represents 70 to 90 percent of the region's livestock—pastoral activities amount to 25 percent of the GDP of Sahelian nations. However, the region’s demographic boom intensifies pressures on food security. The Sahelian population consists of 400 million people and is projected to surpass 500 million by 2050, further straining limited resources. Sahelian agriculture has grown exponentially under these demographic strains, expanding by a factor of 2.5 between 1961 and 2009. Pastoralist communities now face blocked grazing corridors and restricted access to water points, which forces their herds into concentrated areas conducive to unhealthy livestock. Farmers often consider pastoralists as a nuisance or even a threat as roaming cattle can damage cropland through overgrazing. This tension has even occasionally erupted in violence, with pastoralist-farmer clashes resulting in over 15,000 deaths since 2010. With these dynamics set to amplify in the near future, this death toll is expected to increase alongside population growth and desertification.

The Flashpoint

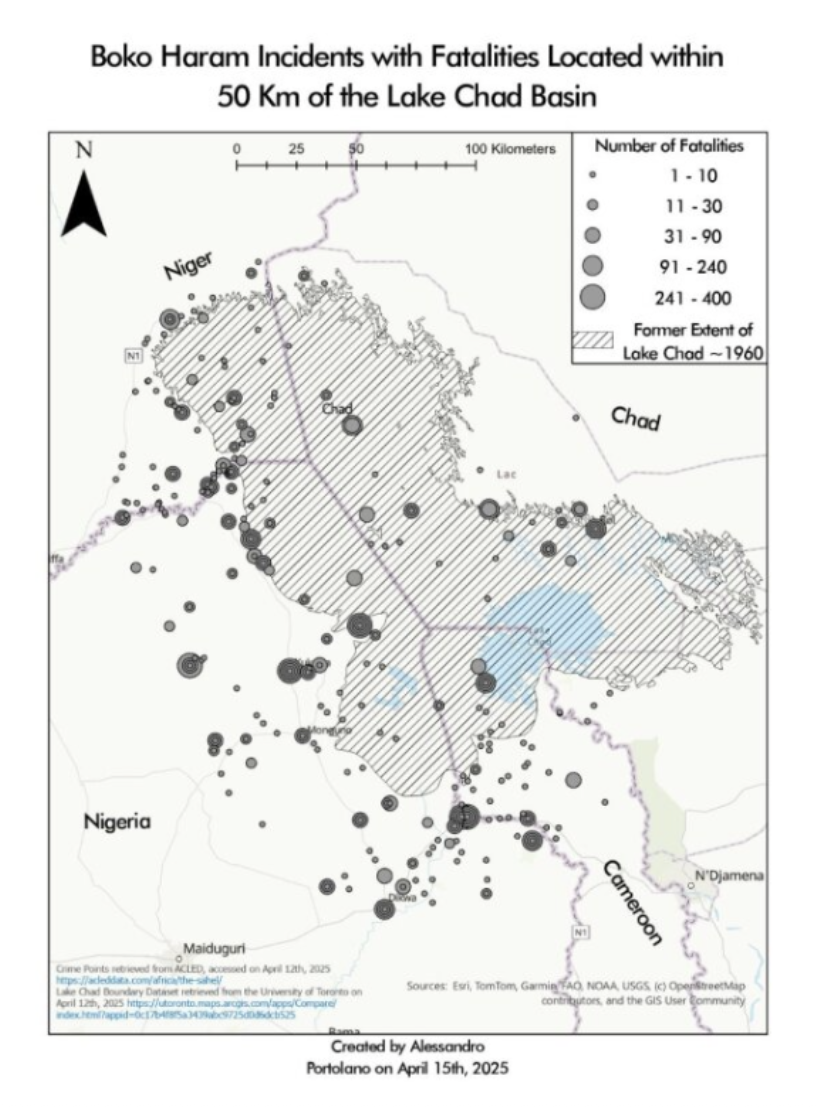

Historically, the Lake Chad Basin has been one of the continent’s foremost sources of freshwater. The lake touches Niger, Nigeria, and Chad, but its basin extends to Algeria, Central African Republic, and Sudan, providing irrigation and personal use for up to 30 million people. Since the 1960s, the lake has lost approximately 90 percent of its surface area as a result of overuse, climate variability, and population growth. The depletion of water resources jeopardizes the livelihood of pastoralists who rely on these resources for their animals. Sahelian nations are no stranger to climate-induced economic misery. A devastating 2010 drought in Niger resulted in the loss of over 4.8 million cattle, representing an economic loss of over $700 million. Amid this backdrop, the diminishing water resources of Lake Chad have granted political capital and strategic advantage to armed groups, such as Boko Haram, who aim to control them. These terrorist actors prey on peripheral regions with endemic corruption and minimal strategic importance to central governments. Controlling water resources is a critical asset in victimizing local populations reliant on a shrinking resource pie. These communities have become targets for Boko Haram’s terror campaign—between 2009 and 2018, violent incidents within a 100-mile radius of Lake Chad led to 15,000 deaths. Since 2009, 152 instances of violent conflict occurred in areas that were underwater as recently as 1973, illustrating the linkage between the lake’s shrinkage and violence. Simultaneously, resource degradation and Islamist violence push pastoralist communities further into the crosshairs of sedentary populations.

Local-level measures in regions dealing with similar problems have enjoyed differing levels of success. Botswana’s government, for example, has taken proactive steps to address extreme weather by integrating drought relief into the national budget, slowly accepting these occurrences as tangible realities. An issue that has risen is the poor documentation of land ownership in the Sahel, which renders binding agreements almost impossible. Makeshift solutions like managing shared fields and demarcating boundaries are complicated when landowners try to reclaim their land from users who “assume that they have acquired some kind of ownership rights over the borrowed land.” Fostering local dispute resolution and minimizing conditions of instability are the first steps in addressing these volatile conditions. While state policies play a crucial role in militating against this form of climate-induced conflict, environmental challenges cannot be resolved through reactive or superficial measures. Effective responses require a long-term policy framework that accounts for complex material conditions and systemic risks. Myopic governance risks overlooking issues whose consequences unfold over extended timelines, undermining sustainable conflict prevention strategies.

Setting a Universal Standard

There is no universally-binding legal framework for transboundary water governance. Though there have been some attempts to create an international standard, these multilateral initiatives have fallen markedly short. The 1992 UN Economic Commission on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes was initially a regional framework, but was later opened for global signatories. Tellingly, the majority of signatories were downstream states, highlighting the privileged strategic position of source nations. Sovereignty remains central to these discussions, often limiting their scope and enforceability. The tricky balance between sovereignty and equal access was highlighted by the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention, which acknowledged the needs and rights of downstream states.

More than 250 river basins cross national borders, necessitating nations to balance their water demands with their neighbors. As the intersection of climate change and conflict becomes more relevant, governments, international organizations, and NGOs must prioritize effective resource governance to ensure environmental security and political stability. In an era of deglobalization, the shared necessity of freshwater can serve as a catalyst for cooperation. The fundamental need for water can transform these risks into opportunities for a more cooperative global order. Amid the many challenges posed by climate change, water governance has the potential to set the precedent for the international community's ability to shape the future.

Edited by Emma Hopp

Managing Editor: Suravi Kumar